On Christmas morning of 2024, while much of the world was unwrapping presents and sharing laughter, one of the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium’s most beloved residents was receiving his favorite gift of all—neck scratches from his favorite person.

Rebecca Koller, Curator of the Zoo’s Australia and the Islands region, had known koala, Koen, long enough to recognize when something wasn’t right. That morning, as her fingers gently brushed through the thick fur of his neck, she found it.

A lump.

By New Year’s Day, that small lump had grown to the size of a golf ball. And in a matter of days, Koen’s life—and the lives of those who loved him—would change forever.

A Gentle Soul with a Willing Heart

While telling this story, the team in the Australia and the Islands region chuckled, saying that koalas are often considered “untrainable.” Independent by nature, with a strict diet of eucalyptus and a penchant for 22-hour naps, they’re not known for being cooperative participants in their own care. But Koen was different. He loved being scratched and held. He trusted his Animal Care team, and that trust made all the difference.

When Koen arrived from the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo in January 2023, the Animal Care team identified something unusual about how he perched. He seemed almost “double-jointed,” not using his front limbs the way most koalas do. Diagnostic tests revealed he had metabolic bone disease, a common condition in koalas treated with Vitamin D treatment and UV light therapy...both of which Koen received.

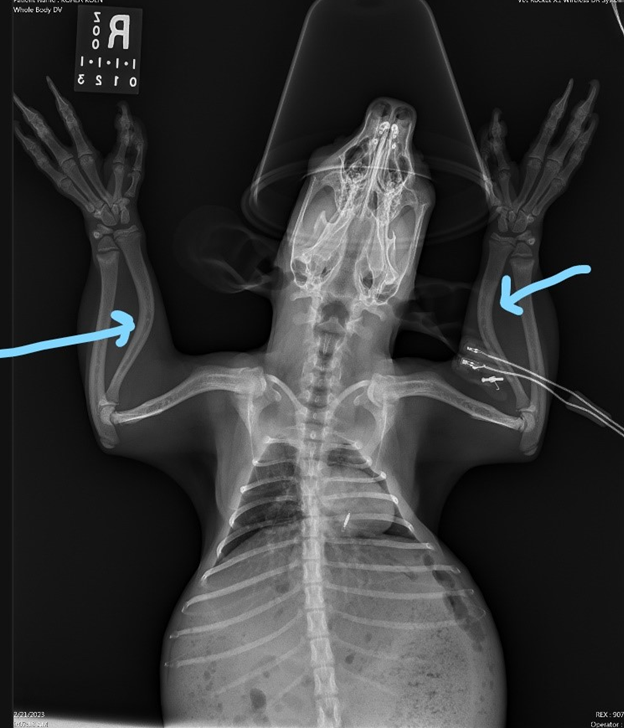

This marked the beginning of something special—a yearlong effort to train Koen for voluntary medical participation. With patience, creativity, a lot of fresh eucalyptus, and a few washcloths scented with the female koalas’ aroma, the team helped Koen learn to stand for X-rays and offer his steady arm for blood draws. Eventually, he became the first koala at the Columbus Zoo to give blood voluntarily.

That alone was remarkable.

A First for Koalas

After the mass in his neck was surgically removed and sent for testing, the results were clear and devastating: lymphoma. A retrovirus common in koalas had activated in Koen’s body, and it was aggressive.

The Zoo's veterinary team consulted and teamed up with oncologists from MedVet, who quickly became part of Koen’s extended family. The decision was made to try something rarely documented before—chemotherapy for a koala.

Because of the bond Koen had with his care team, and the training he’d already mastered, he was able to participate in his own chemo treatments at the Zoo. A vascular access port was placed that led directly to his heart, allowing chemotherapy to be delivered through a carefully timed procedure. Koen handled it all with the quiet dignity that made him so loved. He ate well afterward, accepted his medications, and continued to enjoy his time with the team, often motivated by nothing more than a neck scratch (and the occasional scent of a female koala).

Because this cancer was so aggressive, the goal of treatment wasn’t to cure—it was to give Koen more time, with good quality of life, surrounded by the people and routines he trusted.

And it worked—for a while.

Grief and Gratitude

Despite every effort, the cancer spread quickly. Just over a month after his diagnosis, Koen passed away. The team made the heartbreaking decision for humane euthanasia when it became clear that his quality of life could no longer be preserved.

The grief was deep and raw. Koen was a friend. A partner in conservation. A daily source of joy. The Columbus Zoo provided therapy opportunities for staff members, helping them cope with the loss. But, even now, there’s a quiet void in the space Koen once occupied.

But out of heartbreak came something powerful: hope.

Koen’s story—and everything his care team learned during his treatment—has been shared with other zoos accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). His willingness to trust, his team’s innovative training approach, and the compassion poured into every step of his care are already shaping how other koalas may be helped in the future. In fact, using the same training techniques developed with Koen, the team recently completed a voluntary blood collection with another koala at the Columbus Zoo, Katy—a headstrong female previously thought to be too set in her ways to participate.

A Lasting Legacy

Soon, a new male koala will arrive from the Louisville Zoo. He’ll have his own quirks, his own preferences, and his own story to tell. But Koen will always be there—in the way the team approaches training, in every eucalyptus-scented enrichment, and in every neck scratch given with love. He showed us that “untrainable” doesn’t mean “impossible.” That trust can overcome fear. And that even in the face of an incurable illness, kindness, and innovation can pave the way for something greater.

Koen may be gone, but his legacy is just beginning.